Recently, my colleague Tom Buhrmann wrote A Primer on Private Equity. At a high level, he covers reasons why some investors should consider private equity investing, what the different types of private equity are, and private equity structures.

However, investing in traditional private equity comes with additional complexity compared to investing in public equity (such as individual stocks, equity mutual funds, and ETFs). While there are many differences between public and private investing, the purpose of this piece is to examine three of the most important ones that investors should consider: types of diversification, cash flows, and operational hurdles.

Diversification

To achieve diversification in public market equities, investors can hold individual stocks or funds across a wide range of company sizes, sectors, and geographies. They may also invest in different types of investment styles, such as “value” or “growth.” It is relatively easy to get this diversification through mutual funds or ETFs – many funds own hundreds if not thousands of individual companies.

In traditional private equity investing, there are additional layers of diversification to consider. One of the most important areas to diversify is vintage year risk. In public markets, when you buy an equity, mutual fund, ETF, etc., you own that investment at the time of purchase – with essentially an unlimited time horizon.

In traditional private equity (and other private investment) funds, when you invest in a fund, you commit to having your capital called over time (usually a 3- to 5-year period), with the fund returning your capital in the future (typically over 10 years). This type of fund structure is called a drawdown fund and has historically been a prevalent structure in private equity investing. Under this structure, private equity managers are subject to the market environment when they invest and when they exit an investment. What if the investment period when the private equity fund was investing was bad?

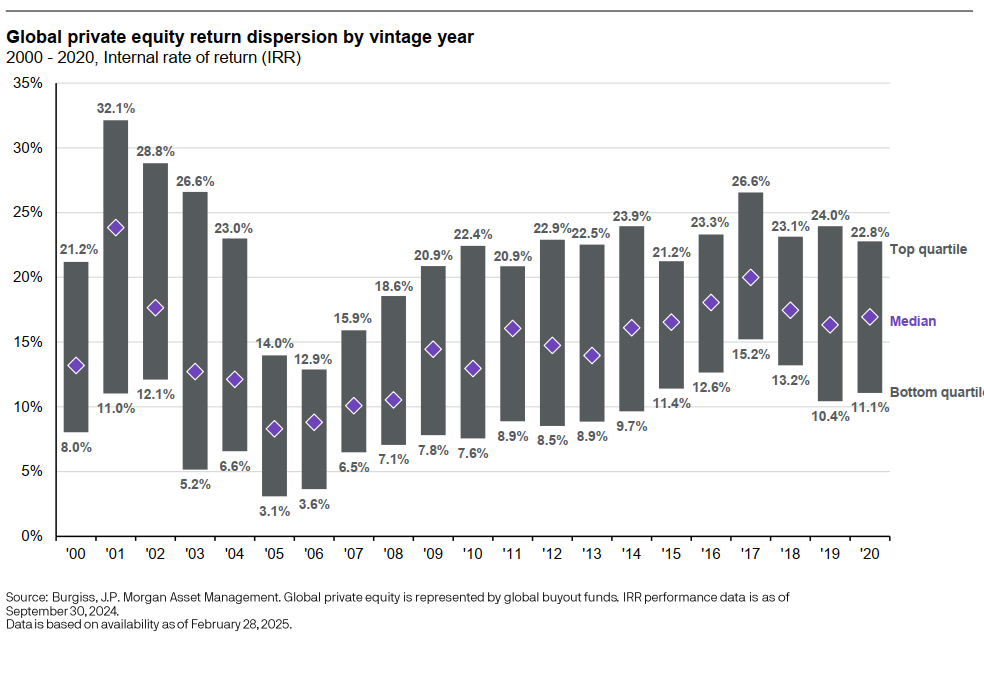

Here is a chart from JP Morgan showing the returns of different vintage years from 2000 – 2020 (returns are through September of 2024):

This chart highlights the reason for vintage year diversification. The “worst” funds in some of the years (2016/2017) can perform just as well (or even better) than the best funds in a bad vintage year (2005/2006).

When you invest in a traditional drawdown private equity fund can often be as important as what the private equity fund invests in! This is why it can be important to diversify by commitment period (or vintage) – investing in multiple funds over time. This can help diversify the risk of investing your entire private equity allocation in a single vintage year – which could turn out to be a bad vintage. Only investing in one vintage could lead to a much wider degree of outcomes.

Cash Flows

As mentioned above, when an investment is made in public equities, money is put to work immediately, and the investment is owned until the investor decides to sell it. Conversely, in traditional drawdown private equity funds, when an investor invests in a private equity fund, they make a commitment to that fund, and those funds call capital over time. An investor might only have 10-20% of their investment called in year 1, and the remaining investment called in the next few years. When the fund calls money, the investor needs to have the money available to meet those capital calls.

Besides being more complex from an operational perspective (more on this in the next section), the investor needs to decide HOW to invest the non-called money in the interim. Should the committed money be invested in public equity? Maybe, but what happens if public equity markets fall and the investor is not able to meet the capital calls from the PE fund? Conversely, investors could miss out on returns if the market moves up significantly and they are holding cash to deploy for future capital calls.

Also, because of the cash flows, how should an investor compare the performance of a drawdown fund versus a non-drawdown fund? Due to the irregular cash flows of traditional drawdown funds, their performance is often measured by their net internal rate of return (IRR) – this is a money weighted measure of performance.

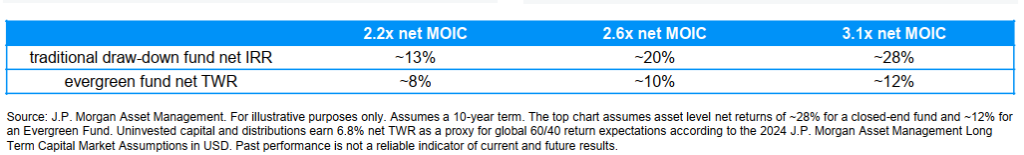

Most public investments, such as stocks and bonds (which are non-drawdown), are measured by their return over a specific time period or time-weighted return (TWR). Due to these differences in return calculations, JP Morgan (and others) have looked at the “Multiple of Invested Capital” (MOIC) to compare a drawdown investment to a non-drawdown investment. Here is JP Morgan’s analysis comparing IRR to TWR over a 10-year period:

This chart shows that for a net MOIC of 2.2x, a net IRR of ~13% is equivalent to a TWR of ~8%. Meaning the drawdown investment’s IRR needs to be at least 13% to be equivalent to an evergreen investment (stock, mutual fund, ETF, etc.) that returns 8% over the period. Granted, there are many assumptions involved with this analysis, but others, such as Cliffwater, KKR, and Neuberger Berman have shown similar results.[1] The bottom line is that because non-drawdown funds put money to work immediately, a lower TWR vs a higher IRR in a drawdown structure will give a similar MOIC.

Operational Hurdles

The last area to touch on is some of the operational obstacles of investing in traditional private equity. Due to the potential operational difficulties, many investors choose not to invest in private equity funds.

Some of these challenges are below:

- High Investment Minimums

- Many private equity funds have high investment minimums – often upwards of $500K (per fund) or more. It may be difficult to achieve diversification (such as vintage year diversification) with fund minimums being so high.

- Tax Reporting – K-1 vs. 1099

- With private investments, it is not uncommon for the investor to receive a K-1 tax form for EACH private investment they are in (versus a 1099 form from a brokerage firm that has the information on all of the public investments at said brokerage firm). The K-1s often come well after the normal 4/15 tax filing deadline, so investors will need to file an extension. If you plan on investing in traditional private equity, you should be aware of the differences.

- Paperwork

- Investing in traditional private equity (and other private funds) typically comes with paperwork on top of paperwork that needs to be filled out. Sometimes the documents can be hundreds of pages long and require dozens of signatures.

- Investor Qualification

- To invest in most traditional private equity funds, an investor needs to be considered a “Qualified Purchaser” (QP). Defining a QP goes beyond the scope of this blog, but generally, an individual with over $5 million of investable assets (not net worth), is considered a QP.

Conclusion

These are just some of the areas investors should be mindful of when thinking about a potential private equity investment. The good news is that over recent years, there has been an evolution in private equity (and other private markets) investing as there are many new(ish) structures that are available to investors that can make the asset class more available and easier to invest in.

If you would like to learn more about how we think of investing in private equity, please reach out to us.

[1]Apples and IRRanges: Peeling Back the Challenges of Performance Measurement in Private Markets (Link)

Disclosure:

This article contains general information that is not suitable for everyone. The information contained herein should not be constructed as personalized investment advice. Reading or utilizing this information does not create an advisory relationship. An advisory relationship can be established only after the following two events have been completed (1) our thorough review with you of all the relevant facts pertaining to a potential engagement; and (2) the execution of a Client Advisory Agreement. There is no guarantee that the views and opinions expressed in this article will come to pass. Investing in the stock market involves gains and losses and may not be suitable for all investors. Information presented herein is subject to change without notice and should not be considered as a solicitation to buy or sell any security.

Strategic Wealth Partners (“SWP”) is d/b/a of, and investment advisory services are offered through, Kovitz Investment Group Partners, LLC (“Kovitz), an investment adviser registered with the United States Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). SEC registration does not constitute an endorsement of Kovitz by the SEC nor does it indicate that Kovitz has attained a particular level of skill or ability. The brochure is limited to the dissemination of general information pertaining to its investment advisory services, views on the market, and investment philosophy. Any subsequent, direct communication by SWP with a prospective client shall be conducted by a representative that is either registered or qualifies for an exemption or exclusion from registration in the state where the prospective client resides. For information pertaining to the registration status of Kovitz Investment Group Partners, LLC, please contact SWP or refer to the Investment Advisor Public Disclosure website (http://www.adviserinfo.sec.gov).

For additional information about SWP, including fees and services, send for Kovitz’s disclosure brochure as set forth on Form ADV from Kovitz using the contact information herein. Please read the disclosure brochure carefully before you invest or send money (http://www.stratwealth.com/legal).